Title: A Soulful Journey

Sub: Artist Amos Roger spent a week at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. In this unique facility, he met Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, who founded it as a refuge for those suffering from mental illness, though in fact it barely survives; Victoria, who suffers from schizophrenia and longs to see her estranged daughters; and Julio, who was stripped of all his wealth and abandoned there. Roger shares his impressions of his encounter with these admirable and sorrowful figures who spend their entire lives trapped between hallucination and reality — and it is impossible to tell which hurts more.

Text and photos: Amos Roger

Text:

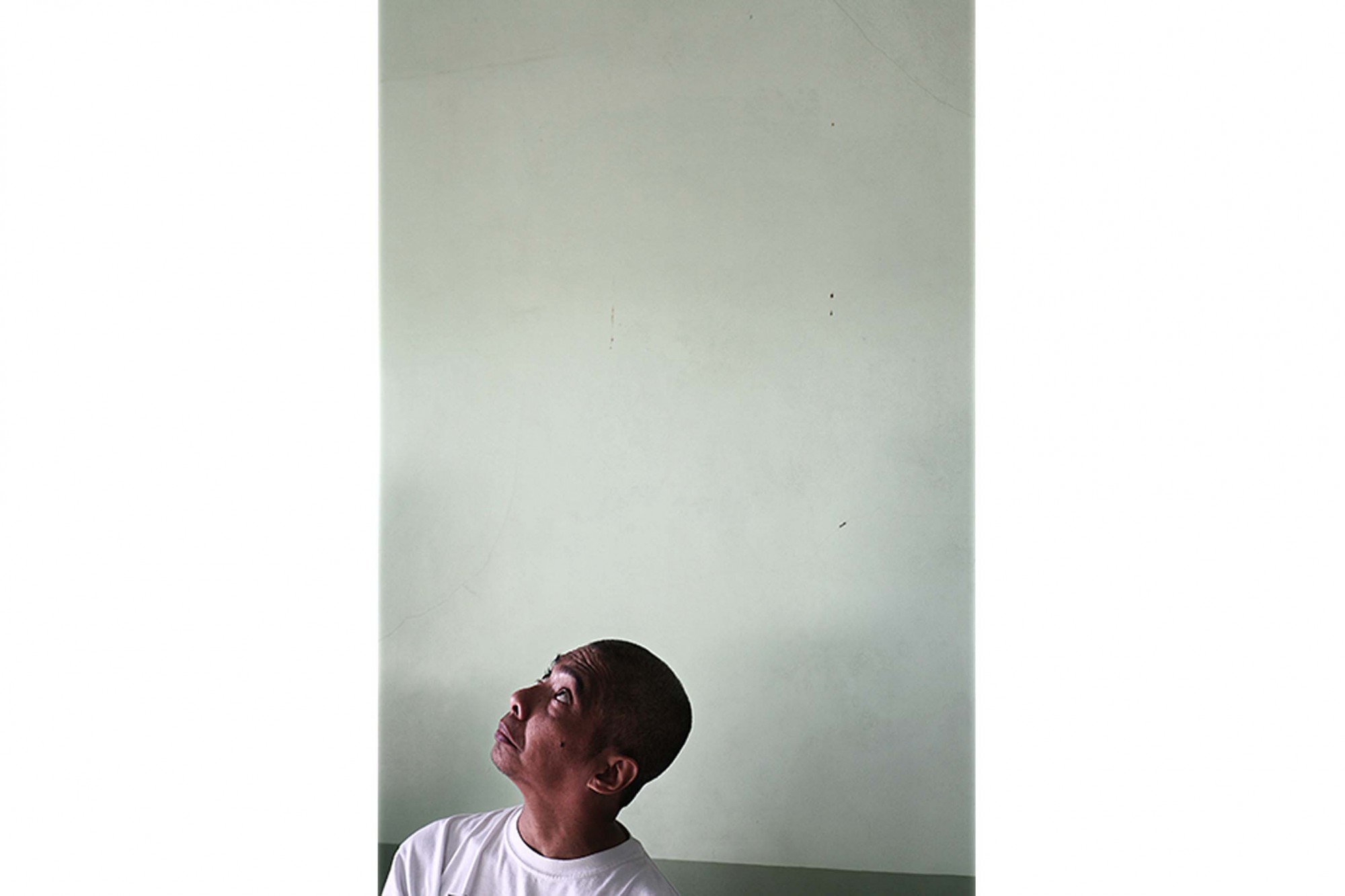

Julio Belanio sits naked on an old wooden bunk bed. His back is bruised, his gaze vacant — and his thoughts in another world. He is not aware of those around him, and he does not notice the bars on the surrounding windows. The drugs he takes first thing in the morning and at night grant him a precious few moments of grace and ease the unending struggle with the disease. As usual, he refuses the nurse’s pleas to cover himself with a blanket.

Ten long years have passed since he was left by his family at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. Who knows if they would have abandoned him in this way if Julio had not been heir to what is, in local terms, a real estate fortune. Disoriented and exhausted from the schizophrenic attacks, they forced him to sign a contract dispossessing him of all his wealth, and left him on the doorstep of the facility. He has not heard a word from them since.

Section Heading: Prison of the Soul

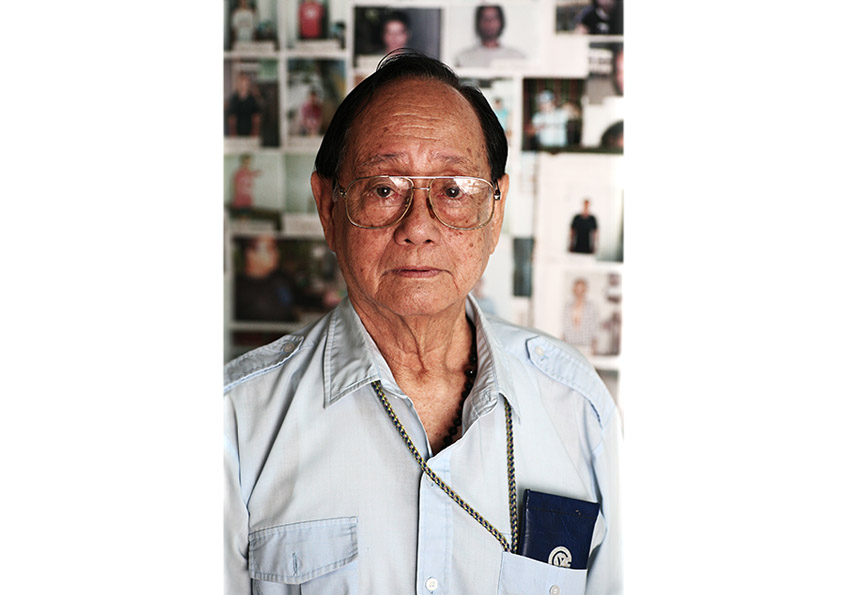

Julio and other patients whom life has broken and bent receive aid and support from the dedicated staff of the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill, located at the southern tip of the main island in the Visayan Islands in the Philippines. It was established two decades ago by Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, and has since cared from more than 5,000 patients. Up until fourteen years ago, the center was run out of prison cells at the local police station, and patients shared cells with local criminals. Dela Llana, previously a practicing dentist, was the force behind the founding of this unique center when he served as the city's deputy mayor. Dr. Dela Llana’s interest in the mentally ill began when he treated them in his dental clinic, part of the municipal health clinic, between 1956-1980. “I learned to love ‘the people wandering in the streets,’” he said. “Those who wander among us doing nothing. I pitied them. I used to bring them food and a little money. When I was chosen as a member of the city council in the eighties, I decided to start a project for those people: a mental health center.” When he failed to find funding for the project, he related, he made up the difference from his own salary.

Economic problems and the difficulty of finding a home for the patients led to prison cells in the local police headquarters serving as a makeshift facility. In order to have time with the patients, Dr. Dela Llana’s workers would bribe the prisoners with cigarettes and sweets — so that, if only for a few moments, they would be occupied with something else. During this time, the staff washed the inmates, and thanks to the medication they gave them, allowed the patients to have “a normal life.” The first signs of change appeared when they began receiving government support: a grant of 237,000 pesos, thanks to which they succeeded in building a six-room structure. At the same time, the city of Iloilo paid for the salaries of fourteen therapists. Only years later did Dr. Dela Llana succeed in building two more floors, the last paid for from his own pocket.

Section Heading: Forecast: No Change

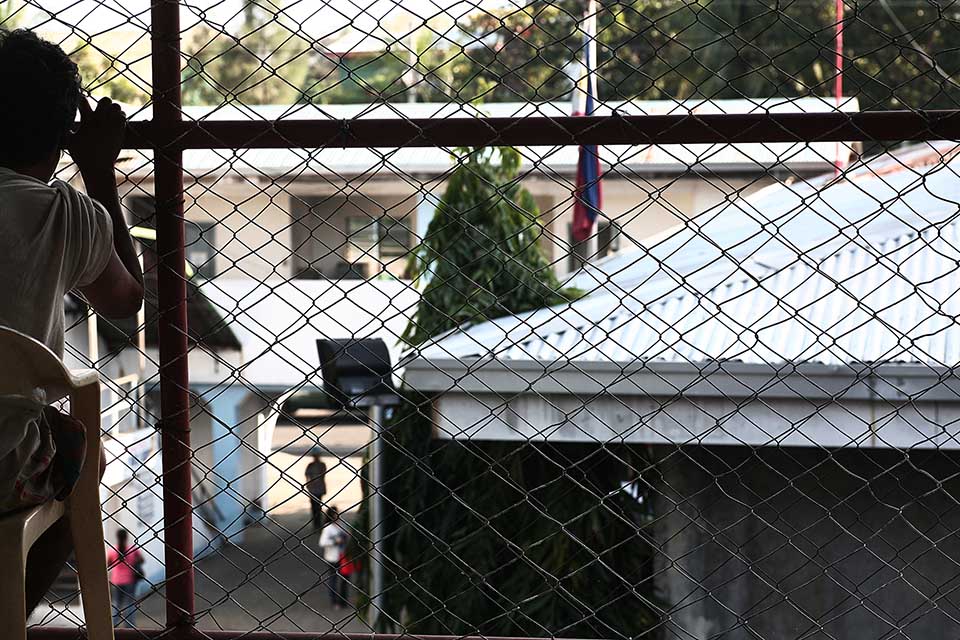

Patients meet with a licensed psychiatrist once a month at the Done-Benito government hospital. The hospital is a short distance away, and during the journey Julio and his friends receive a small, fleeting taste of the world outside. During the ride, absolute silence reigns in the car, and frozen glances stare at the sights through the windows. But on the inside — spiritual turmoil and a powerful longing to become once again a part of those scenes.

When they arrive at the hospital, an interminable line stretches down the hallway, and even the room itself is too small. Privacy is nonexistent. Psychology students wearing white gowns listen attentively to the patients. All the conversations take place in parallel — three students sit in the room, in front of them three patients, and behind them many more.

Victoria Muya is also in the room, turning around in excitement. In honor of the trip she wore a red dress and put on red lipstick. She, too, suffers from schizophrenia, which for her is characterized by chronic depression. It reached its height when her husband tired of taking care of her and left her for another woman. She has two daughters who have not visited her since she was hospitalized. Once, in another time, she worked in her aunt's grocery store. Now, she spends most of her time resting in her room and on the center's rooftop balcony on the third floor, giving herself up to the caresses of the sun.

Section Heading: The World Can Change in a Moment

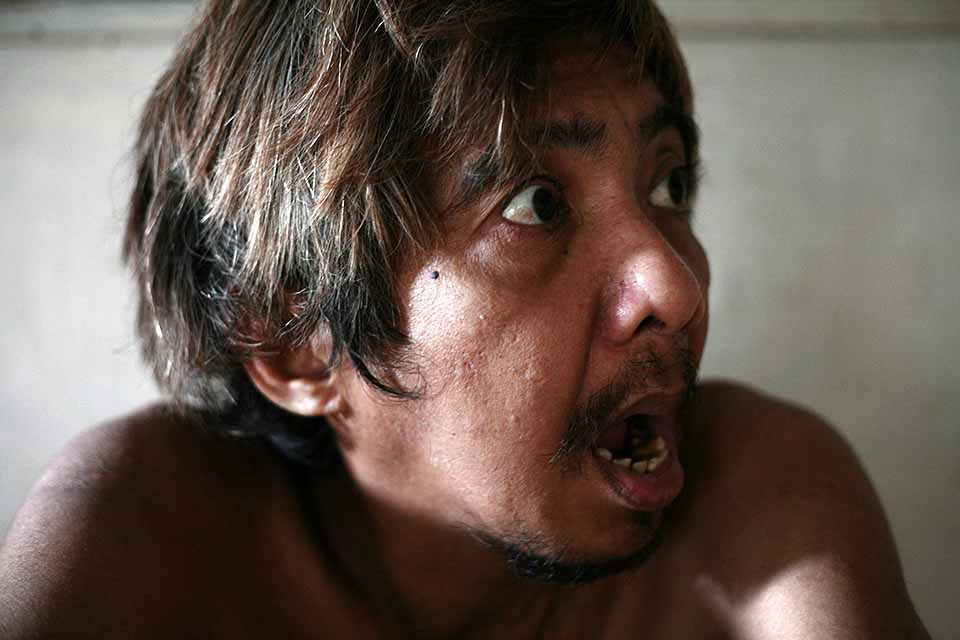

Roman Bernas’s illness first appeared fifteen years ago, during the third year of his studies in the university’s faculty of engineering. He has two brothers and two sisters — Priscilla and Florence — both of whom are diagnosed with the same disease. In their youth, they were raped by one of their neighbors. The youngest sister, Florence, remains with Roman at the center. Priscilla was released. Roman came to the center almost ten years ago, not knowing that his sister lived at the other end of the hall. He also does not remember that in the past they used to have sexual relations, even when their mother was at home.

Milagros-Seyan, Dr. Dela Llana’s daughter, who has run the day-to-day operations at the center since 2005, told me that Roman is the most difficult patient. “Roman is very unpredictable,” she said. “For days on end he is content and quiet. And then, all of a sudden, his disease strikes. He lashes out and hits other patients.” Seyan explained that his violent outbursts are the reason why he spends most of his time in solitary confinement.

The local residents know of the center's activities; it has become famous in the surrounding region. In the beginning, the center only accepted people suffering from mental illness. But over the years, Dr. Dela Llana decided also to rehabilitate those addicted to drugs. “The mentally ill generally arrive at their families’ initiative,” the doctor said. “However, the local police in Iloilo bring the patients suffering from addiction to drugs or alcohol, and they are the ones who recommend needy patients to me. Rarely, when there is no space left in the center and a new patient comes who requires urgent help, I'm forced to release a different patient who has improved. These are the most disappointing situations, because it is so important to me to lighten the load on the families as much as possible; if only I could satisfy everyone.”

One of the new addicts in the center is Rotehel Barrera. Barrera is addicted to shabu, a type of narcotic that is widely used in the Philippines and throughout Southeast Asia. He has been addicted for five years. In order to buy drugs, Barrera would often steal electronics from his parents’ home and even sell his blood to a blood bank. Last year his father suffered a stroke, and the family believes that there is connection between Barrera's decline over the past year and his father’s health.

His behavior is characterized by extreme emotional states. One minute he is able to focus on a complicated move in chess, and the next he is violent and dangerous to those around him. He will attack and provoke anyone nearby. In such situations, workers are forced to call for his mother and sister to remind him why he is hospitalized.

Nevertheless, Barrera does not understand why he is kept at the center. He announces again and again that “even the bird in the cage wants to go free.” Seyan insists that he is not yet ready to return to normal life. “The moment that he decides to take matters into his own hands and to stop the pain he is causing himself and his family, then he will succeed in being rehabilitated,” she explained. “For now, whenever he had an opportunity to take drugs, he did not hesitate.”

Section Heading: Missing Mother

A new morning at the center. Julio, Roman, and other patients go up to the attic. There, they will receive private therapy from the psychology students who provide them with the attention they need and most importantly, try to help them to acquire hygienic habits. They wash them, change their dirty clothes, and trim their fingernails, all the while hoping that their situation will improve by the next visit.

Charlito Magallanes, too, has his fingernails trimmed in the attic. He has been a patient at the center for almost five years, trying to quit drugs, passing his days between serene joie de vivre and acute aggression. Magallanes’s excessive drug use caused irreversible damage and impaired the proper functioning of part of his brain. He does not recognize his mother. Basic, everyday decisions are difficult for him, especially those connected to hygiene. The medical staff are not optimistic. Most believe that Magallanes’s chances for recovery are slim and expect a long and difficult rehabilitation.

Treating patients requires medication, food, visits to the psychiatrist, and round-the-clock observation. Because of the small budget at the staff's disposal, many families of patients face a choice: whether or not to pay for their loved one's treatment themselves, thus ensuring a personalized treatment regimen that will increase the chances of recovery. When families do not have the means, or are not involved, the doctor makes up the difference from his own pocket.

The budget depends on the city and its mayor’s willingness to help. At the moment, there is a good working relationship between Dr. Dela Llana and the mayor, Jerry P. Trenas, but if another mayor is elected, the municipal funding could decrease. “I am already 81,” Dela Llana said. “What worries me more than anything else is that I could depart this world at any moment. When it happens, who will care for the center, who will invest the money?”

The Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill wants to provide running water, to install a kitchen, to enlarge the stocks of medication, to hire a staff psychiatrist, and, most of all, to build a courtyard where the patients can get fresh air.

Address: Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill, Iloilo Police Station, General Luna Street, Iloilo City

Telephone: ++63-3372381 / ++63-3374073

Mobile: ++63-9279456936

Email: siroy_gylaine@yahoo.com; mentalill_center@yahoo.com

Text Box Explaining the Condition

Schizophrenia is a widespread, chronic mental illness classified as a psychosis. The disease affects most areas of mental and social functioning: mood, sensation, perception, thought, as well as cognitive functions. Schizophrenics distance themselves from reality, think in a disorganized and illogical way, and suffer from hallucinations and delusions. The term “schizophrenia” was coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Paul Eugen Bleuler. Despite widespread misconception, schizophrenia is not “multiple personality disorder.” Schizophrenics make up 1-1.5% of the population, and are found equally among both sexes, though there are differences in the disease's appearance and characteristics. Schizophrenia strikes young people most of all: among men, the disease mostly manifests itself between the ages of fifteen to twenty-five, and in these cases there is a high likelihood of developing negative symptoms, including emotional flattening or blunting; “poverty” of speech or language, whether in content or manner; blocks (in speaking); self-neglect (poor hygiene, sloppy dressing); lack of motivation; general lack of satisfaction; and social distancing. Among women, the disease mostly manifests between the ages of 25-35, and they have a higher chance of developing positive symptoms including delusions and hallucinations. The disease is connected to a chemical imbalance in the brain, and can be aided with medication that significantly improves the condition.

All contents © copyright Amos Roger. 2024 All rights reserved

All contents © copyright Amos Roger. 2024 All rights reservedTitle: A Soulful Journey

Sub: Artist Amos Roger spent a week at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. In this unique facility, he met Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, who founded it as a refuge for those suffering from mental illness, though in fact it barely survives; Victoria, who suffers from schizophrenia and longs to see her estranged daughters; and Julio, who was stripped of all his wealth and abandoned there. Roger shares his impressions of his encounter with these admirable and sorrowful figures who spend their entire lives trapped between hallucination and reality — and it is impossible to tell which hurts more.

Text and photos: Amos Roger

Text:

Julio Belanio sits naked on an old wooden bunk bed. His back is bruised, his gaze vacant — and his thoughts in another world. He is not aware of those around him, and he does not notice the bars on the surrounding windows. The drugs he takes first thing in the morning and at night grant him a precious few moments of grace and ease the unending struggle with the disease. As usual, he refuses the nurse’s pleas to cover himself with a blanket.

Ten long years have passed since he was left by his family at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. Who knows if they would have abandoned him in this way if Julio had not been heir to what is, in local terms, a real estate fortune. Disoriented and exhausted from the schizophrenic attacks, they forced him to sign a contract dispossessing him of all his wealth, and left him on the doorstep of the facility. He has not heard a word from them since.

Section Heading: Prison of the Soul

Julio and other patients whom life has broken and bent receive aid and support from the dedicated staff of the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill, located at the southern tip of the main island in the Visayan Islands in the Philippines. It was established two decades ago by Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, and has since cared from more than 5,000 patients. Up until fourteen years ago, the center was run out of prison cells at the local police station, and patients shared cells with local criminals. Dela Llana, previously a practicing dentist, was the force behind the founding of this unique center when he served as the city's deputy mayor. Dr. Dela Llana’s interest in the mentally ill began when he treated them in his dental clinic, part of the municipal health clinic, between 1956-1980. “I learned to love ‘the people wandering in the streets,’” he said. “Those who wander among us doing nothing. I pitied them. I used to bring them food and a little money. When I was chosen as a member of the city council in the eighties, I decided to start a project for those people: a mental health center.” When he failed to find funding for the project, he related, he made up the difference from his own salary.

Economic problems and the difficulty of finding a home for the patients led to prison cells in the local police headquarters serving as a makeshift facility. In order to have time with the patients, Dr. Dela Llana’s workers would bribe the prisoners with cigarettes and sweets — so that, if only for a few moments, they would be occupied with something else. During this time, the staff washed the inmates, and thanks to the medication they gave them, allowed the patients to have “a normal life.” The first signs of change appeared when they began receiving government support: a grant of 237,000 pesos, thanks to which they succeeded in building a six-room structure. At the same time, the city of Iloilo paid for the salaries of fourteen therapists. Only years later did Dr. Dela Llana succeed in building two more floors, the last paid for from his own pocket.

Section Heading: Forecast: No Change

Patients meet with a licensed psychiatrist once a month at the Done-Benito government hospital. The hospital is a short distance away, and during the journey Julio and his friends receive a small, fleeting taste of the world outside. During the ride, absolute silence reigns in the car, and frozen glances stare at the sights through the windows. But on the inside — spiritual turmoil and a powerful longing to become once again a part of those scenes.

When they arrive at the hospital, an interminable line stretches down the hallway, and even the room itself is too small. Privacy is nonexistent. Psychology students wearing white gowns listen attentively to the patients. All the conversations take place in parallel — three students sit in the room, in front of them three patients, and behind them many more.

Victoria Muya is also in the room, turning around in excitement. In honor of the trip she wore a red dress and put on red lipstick. She, too, suffers from schizophrenia, which for her is characterized by chronic depression. It reached its height when her husband tired of taking care of her and left her for another woman. She has two daughters who have not visited her since she was hospitalized. Once, in another time, she worked in her aunt's grocery store. Now, she spends most of her time resting in her room and on the center's rooftop balcony on the third floor, giving herself up to the caresses of the sun.

Section Heading: The World Can Change in a Moment

Roman Bernas’s illness first appeared fifteen years ago, during the third year of his studies in the university’s faculty of engineering. He has two brothers and two sisters — Priscilla and Florence — both of whom are diagnosed with the same disease. In their youth, they were raped by one of their neighbors. The youngest sister, Florence, remains with Roman at the center. Priscilla was released. Roman came to the center almost ten years ago, not knowing that his sister lived at the other end of the hall. He also does not remember that in the past they used to have sexual relations, even when their mother was at home.

Milagros-Seyan, Dr. Dela Llana’s daughter, who has run the day-to-day operations at the center since 2005, told me that Roman is the most difficult patient. “Roman is very unpredictable,” she said. “For days on end he is content and quiet. And then, all of a sudden, his disease strikes. He lashes out and hits other patients.” Seyan explained that his violent outbursts are the reason why he spends most of his time in solitary confinement.

The local residents know of the center's activities; it has become famous in the surrounding region. In the beginning, the center only accepted people suffering from mental illness. But over the years, Dr. Dela Llana decided also to rehabilitate those addicted to drugs. “The mentally ill generally arrive at their families’ initiative,” the doctor said. “However, the local police in Iloilo bring the patients suffering from addiction to drugs or alcohol, and they are the ones who recommend needy patients to me. Rarely, when there is no space left in the center and a new patient comes who requires urgent help, I'm forced to release a different patient who has improved. These are the most disappointing situations, because it is so important to me to lighten the load on the families as much as possible; if only I could satisfy everyone.”

One of the new addicts in the center is Rotehel Barrera. Barrera is addicted to shabu, a type of narcotic that is widely used in the Philippines and throughout Southeast Asia. He has been addicted for five years. In order to buy drugs, Barrera would often steal electronics from his parents’ home and even sell his blood to a blood bank. Last year his father suffered a stroke, and the family believes that there is connection between Barrera's decline over the past year and his father’s health.

His behavior is characterized by extreme emotional states. One minute he is able to focus on a complicated move in chess, and the next he is violent and dangerous to those around him. He will attack and provoke anyone nearby. In such situations, workers are forced to call for his mother and sister to remind him why he is hospitalized.

Nevertheless, Barrera does not understand why he is kept at the center. He announces again and again that “even the bird in the cage wants to go free.” Seyan insists that he is not yet ready to return to normal life. “The moment that he decides to take matters into his own hands and to stop the pain he is causing himself and his family, then he will succeed in being rehabilitated,” she explained. “For now, whenever he had an opportunity to take drugs, he did not hesitate.”

Section Heading: Missing Mother

A new morning at the center. Julio, Roman, and other patients go up to the attic. There, they will receive private therapy from the psychology students who provide them with the attention they need and most importantly, try to help them to acquire hygienic habits. They wash them, change their dirty clothes, and trim their fingernails, all the while hoping that their situation will improve by the next visit.

Charlito Magallanes, too, has his fingernails trimmed in the attic. He has been a patient at the center for almost five years, trying to quit drugs, passing his days between serene joie de vivre and acute aggression. Magallanes’s excessive drug use caused irreversible damage and impaired the proper functioning of part of his brain. He does not recognize his mother. Basic, everyday decisions are difficult for him, especially those connected to hygiene. The medical staff are not optimistic. Most believe that Magallanes’s chances for recovery are slim and expect a long and difficult rehabilitation.

Treating patients requires medication, food, visits to the psychiatrist, and round-the-clock observation. Because of the small budget at the staff's disposal, many families of patients face a choice: whether or not to pay for their loved one's treatment themselves, thus ensuring a personalized treatment regimen that will increase the chances of recovery. When families do not have the means, or are not involved, the doctor makes up the difference from his own pocket.

The budget depends on the city and its mayor’s willingness to help. At the moment, there is a good working relationship between Dr. Dela Llana and the mayor, Jerry P. Trenas, but if another mayor is elected, the municipal funding could decrease. “I am already 81,” Dela Llana said. “What worries me more than anything else is that I could depart this world at any moment. When it happens, who will care for the center, who will invest the money?”

The Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill wants to provide running water, to install a kitchen, to enlarge the stocks of medication, to hire a staff psychiatrist, and, most of all, to build a courtyard where the patients can get fresh air.

Address: Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill, Iloilo Police Station, General Luna Street, Iloilo City

Telephone: ++63-3372381 / ++63-3374073

Mobile: ++63-9279456936

Email: siroy_gylaine@yahoo.com; mentalill_center@yahoo.com

Text Box Explaining the Condition

Schizophrenia is a widespread, chronic mental illness classified as a psychosis. The disease affects most areas of mental and social functioning: mood, sensation, perception, thought, as well as cognitive functions. Schizophrenics distance themselves from reality, think in a disorganized and illogical way, and suffer from hallucinations and delusions. The term “schizophrenia” was coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Paul Eugen Bleuler. Despite widespread misconception, schizophrenia is not “multiple personality disorder.” Schizophrenics make up 1-1.5% of the population, and are found equally among both sexes, though there are differences in the disease's appearance and characteristics. Schizophrenia strikes young people most of all: among men, the disease mostly manifests itself between the ages of fifteen to twenty-five, and in these cases there is a high likelihood of developing negative symptoms, including emotional flattening or blunting; “poverty” of speech or language, whether in content or manner; blocks (in speaking); self-neglect (poor hygiene, sloppy dressing); lack of motivation; general lack of satisfaction; and social distancing. Among women, the disease mostly manifests between the ages of 25-35, and they have a higher chance of developing positive symptoms including delusions and hallucinations. The disease is connected to a chemical imbalance in the brain, and can be aided with medication that significantly improves the condition.

All contents © copyright Amos Roger. 2024 All rights reserved

All contents © copyright Amos Roger. 2024 All rights reservedTitle: A Soulful Journey

Sub: Artist Amos Roger spent a week at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. In this unique facility, he met Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, who founded it as a refuge for those suffering from mental illness, though in fact it barely survives; Victoria, who suffers from schizophrenia and longs to see her estranged daughters; and Julio, who was stripped of all his wealth and abandoned there. Roger shares his impressions of his encounter with these admirable and sorrowful figures who spend their entire lives trapped between hallucination and reality — and it is impossible to tell which hurts more.

Text and photos: Amos Roger

Text:

Julio Belanio sits naked on an old wooden bunk bed. His back is bruised, his gaze vacant — and his thoughts in another world. He is not aware of those around him, and he does not notice the bars on the surrounding windows. The drugs he takes first thing in the morning and at night grant him a precious few moments of grace and ease the unending struggle with the disease. As usual, he refuses the nurse’s pleas to cover himself with a blanket.

Ten long years have passed since he was left by his family at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. Who knows if they would have abandoned him in this way if Julio had not been heir to what is, in local terms, a real estate fortune. Disoriented and exhausted from the schizophrenic attacks, they forced him to sign a contract dispossessing him of all his wealth, and left him on the doorstep of the facility. He has not heard a word from them since.

Section Heading: Prison of the Soul

Julio and other patients whom life has broken and bent receive aid and support from the dedicated staff of the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill, located at the southern tip of the main island in the Visayan Islands in the Philippines. It was established two decades ago by Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, and has since cared from more than 5,000 patients. Up until fourteen years ago, the center was run out of prison cells at the local police station, and patients shared cells with local criminals. Dela Llana, previously a practicing dentist, was the force behind the founding of this unique center when he served as the city's deputy mayor. Dr. Dela Llana’s interest in the mentally ill began when he treated them in his dental clinic, part of the municipal health clinic, between 1956-1980. “I learned to love ‘the people wandering in the streets,’” he said. “Those who wander among us doing nothing. I pitied them. I used to bring them food and a little money. When I was chosen as a member of the city council in the eighties, I decided to start a project for those people: a mental health center.” When he failed to find funding for the project, he related, he made up the difference from his own salary.

Economic problems and the difficulty of finding a home for the patients led to prison cells in the local police headquarters serving as a makeshift facility. In order to have time with the patients, Dr. Dela Llana’s workers would bribe the prisoners with cigarettes and sweets — so that, if only for a few moments, they would be occupied with something else. During this time, the staff washed the inmates, and thanks to the medication they gave them, allowed the patients to have “a normal life.” The first signs of change appeared when they began receiving government support: a grant of 237,000 pesos, thanks to which they succeeded in building a six-room structure. At the same time, the city of Iloilo paid for the salaries of fourteen therapists. Only years later did Dr. Dela Llana succeed in building two more floors, the last paid for from his own pocket.

Section Heading: Forecast: No Change

Patients meet with a licensed psychiatrist once a month at the Done-Benito government hospital. The hospital is a short distance away, and during the journey Julio and his friends receive a small, fleeting taste of the world outside. During the ride, absolute silence reigns in the car, and frozen glances stare at the sights through the windows. But on the inside — spiritual turmoil and a powerful longing to become once again a part of those scenes.

When they arrive at the hospital, an interminable line stretches down the hallway, and even the room itself is too small. Privacy is nonexistent. Psychology students wearing white gowns listen attentively to the patients. All the conversations take place in parallel — three students sit in the room, in front of them three patients, and behind them many more.

Victoria Muya is also in the room, turning around in excitement. In honor of the trip she wore a red dress and put on red lipstick. She, too, suffers from schizophrenia, which for her is characterized by chronic depression. It reached its height when her husband tired of taking care of her and left her for another woman. She has two daughters who have not visited her since she was hospitalized. Once, in another time, she worked in her aunt's grocery store. Now, she spends most of her time resting in her room and on the center's rooftop balcony on the third floor, giving herself up to the caresses of the sun.

Section Heading: The World Can Change in a Moment

Roman Bernas’s illness first appeared fifteen years ago, during the third year of his studies in the university’s faculty of engineering. He has two brothers and two sisters — Priscilla and Florence — both of whom are diagnosed with the same disease. In their youth, they were raped by one of their neighbors. The youngest sister, Florence, remains with Roman at the center. Priscilla was released. Roman came to the center almost ten years ago, not knowing that his sister lived at the other end of the hall. He also does not remember that in the past they used to have sexual relations, even when their mother was at home.

Milagros-Seyan, Dr. Dela Llana’s daughter, who has run the day-to-day operations at the center since 2005, told me that Roman is the most difficult patient. “Roman is very unpredictable,” she said. “For days on end he is content and quiet. And then, all of a sudden, his disease strikes. He lashes out and hits other patients.” Seyan explained that his violent outbursts are the reason why he spends most of his time in solitary confinement.

The local residents know of the center's activities; it has become famous in the surrounding region. In the beginning, the center only accepted people suffering from mental illness. But over the years, Dr. Dela Llana decided also to rehabilitate those addicted to drugs. “The mentally ill generally arrive at their families’ initiative,” the doctor said. “However, the local police in Iloilo bring the patients suffering from addiction to drugs or alcohol, and they are the ones who recommend needy patients to me. Rarely, when there is no space left in the center and a new patient comes who requires urgent help, I'm forced to release a different patient who has improved. These are the most disappointing situations, because it is so important to me to lighten the load on the families as much as possible; if only I could satisfy everyone.”

One of the new addicts in the center is Rotehel Barrera. Barrera is addicted to shabu, a type of narcotic that is widely used in the Philippines and throughout Southeast Asia. He has been addicted for five years. In order to buy drugs, Barrera would often steal electronics from his parents’ home and even sell his blood to a blood bank. Last year his father suffered a stroke, and the family believes that there is connection between Barrera's decline over the past year and his father’s health.

His behavior is characterized by extreme emotional states. One minute he is able to focus on a complicated move in chess, and the next he is violent and dangerous to those around him. He will attack and provoke anyone nearby. In such situations, workers are forced to call for his mother and sister to remind him why he is hospitalized.

Nevertheless, Barrera does not understand why he is kept at the center. He announces again and again that “even the bird in the cage wants to go free.” Seyan insists that he is not yet ready to return to normal life. “The moment that he decides to take matters into his own hands and to stop the pain he is causing himself and his family, then he will succeed in being rehabilitated,” she explained. “For now, whenever he had an opportunity to take drugs, he did not hesitate.”

Section Heading: Missing Mother

A new morning at the center. Julio, Roman, and other patients go up to the attic. There, they will receive private therapy from the psychology students who provide them with the attention they need and most importantly, try to help them to acquire hygienic habits. They wash them, change their dirty clothes, and trim their fingernails, all the while hoping that their situation will improve by the next visit.

Charlito Magallanes, too, has his fingernails trimmed in the attic. He has been a patient at the center for almost five years, trying to quit drugs, passing his days between serene joie de vivre and acute aggression. Magallanes’s excessive drug use caused irreversible damage and impaired the proper functioning of part of his brain. He does not recognize his mother. Basic, everyday decisions are difficult for him, especially those connected to hygiene. The medical staff are not optimistic. Most believe that Magallanes’s chances for recovery are slim and expect a long and difficult rehabilitation.

Treating patients requires medication, food, visits to the psychiatrist, and round-the-clock observation. Because of the small budget at the staff's disposal, many families of patients face a choice: whether or not to pay for their loved one's treatment themselves, thus ensuring a personalized treatment regimen that will increase the chances of recovery. When families do not have the means, or are not involved, the doctor makes up the difference from his own pocket.

The budget depends on the city and its mayor’s willingness to help. At the moment, there is a good working relationship between Dr. Dela Llana and the mayor, Jerry P. Trenas, but if another mayor is elected, the municipal funding could decrease. “I am already 81,” Dela Llana said. “What worries me more than anything else is that I could depart this world at any moment. When it happens, who will care for the center, who will invest the money?”

The Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill wants to provide running water, to install a kitchen, to enlarge the stocks of medication, to hire a staff psychiatrist, and, most of all, to build a courtyard where the patients can get fresh air.

Address: Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill, Iloilo Police Station, General Luna Street, Iloilo City

Telephone: ++63-3372381 / ++63-3374073

Mobile: ++63-9279456936

Email: siroy_gylaine@yahoo.com; mentalill_center@yahoo.com

Text Box Explaining the Condition

Schizophrenia is a widespread, chronic mental illness classified as a psychosis. The disease affects most areas of mental and social functioning: mood, sensation, perception, thought, as well as cognitive functions. Schizophrenics distance themselves from reality, think in a disorganized and illogical way, and suffer from hallucinations and delusions. The term “schizophrenia” was coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Paul Eugen Bleuler. Despite widespread misconception, schizophrenia is not “multiple personality disorder.” Schizophrenics make up 1-1.5% of the population, and are found equally among both sexes, though there are differences in the disease's appearance and characteristics. Schizophrenia strikes young people most of all: among men, the disease mostly manifests itself between the ages of fifteen to twenty-five, and in these cases there is a high likelihood of developing negative symptoms, including emotional flattening or blunting; “poverty” of speech or language, whether in content or manner; blocks (in speaking); self-neglect (poor hygiene, sloppy dressing); lack of motivation; general lack of satisfaction; and social distancing. Among women, the disease mostly manifests between the ages of 25-35, and they have a higher chance of developing positive symptoms including delusions and hallucinations. The disease is connected to a chemical imbalance in the brain, and can be aided with medication that significantly improves the condition.

All contents © copyright Amos Roger. 2024 All rights reserved

All contents © copyright Amos Roger. 2024 All rights reservedTitle: A Soulful Journey

Sub: Artist Amos Roger spent a week at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. In this unique facility, he met Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, who founded it as a refuge for those suffering from mental illness, though in fact it barely survives; Victoria, who suffers from schizophrenia and longs to see her estranged daughters; and Julio, who was stripped of all his wealth and abandoned there. Roger shares his impressions of his encounter with these admirable and sorrowful figures who spend their entire lives trapped between hallucination and reality — and it is impossible to tell which hurts more.

Text and photos: Amos Roger

Text:

Julio Belanio sits naked on an old wooden bunk bed. His back is bruised, his gaze vacant — and his thoughts in another world. He is not aware of those around him, and he does not notice the bars on the surrounding windows. The drugs he takes first thing in the morning and at night grant him a precious few moments of grace and ease the unending struggle with the disease. As usual, he refuses the nurse’s pleas to cover himself with a blanket.

Ten long years have passed since he was left by his family at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. Who knows if they would have abandoned him in this way if Julio had not been heir to what is, in local terms, a real estate fortune. Disoriented and exhausted from the schizophrenic attacks, they forced him to sign a contract dispossessing him of all his wealth, and left him on the doorstep of the facility. He has not heard a word from them since.

Section Heading: Prison of the Soul

Julio and other patients whom life has broken and bent receive aid and support from the dedicated staff of the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill, located at the southern tip of the main island in the Visayan Islands in the Philippines. It was established two decades ago by Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, and has since cared from more than 5,000 patients. Up until fourteen years ago, the center was run out of prison cells at the local police station, and patients shared cells with local criminals. Dela Llana, previously a practicing dentist, was the force behind the founding of this unique center when he served as the city's deputy mayor. Dr. Dela Llana’s interest in the mentally ill began when he treated them in his dental clinic, part of the municipal health clinic, between 1956-1980. “I learned to love ‘the people wandering in the streets,’” he said. “Those who wander among us doing nothing. I pitied them. I used to bring them food and a little money. When I was chosen as a member of the city council in the eighties, I decided to start a project for those people: a mental health center.” When he failed to find funding for the project, he related, he made up the difference from his own salary.

Economic problems and the difficulty of finding a home for the patients led to prison cells in the local police headquarters serving as a makeshift facility. In order to have time with the patients, Dr. Dela Llana’s workers would bribe the prisoners with cigarettes and sweets — so that, if only for a few moments, they would be occupied with something else. During this time, the staff washed the inmates, and thanks to the medication they gave them, allowed the patients to have “a normal life.” The first signs of change appeared when they began receiving government support: a grant of 237,000 pesos, thanks to which they succeeded in building a six-room structure. At the same time, the city of Iloilo paid for the salaries of fourteen therapists. Only years later did Dr. Dela Llana succeed in building two more floors, the last paid for from his own pocket.

Section Heading: Forecast: No Change

Patients meet with a licensed psychiatrist once a month at the Done-Benito government hospital. The hospital is a short distance away, and during the journey Julio and his friends receive a small, fleeting taste of the world outside. During the ride, absolute silence reigns in the car, and frozen glances stare at the sights through the windows. But on the inside — spiritual turmoil and a powerful longing to become once again a part of those scenes.

When they arrive at the hospital, an interminable line stretches down the hallway, and even the room itself is too small. Privacy is nonexistent. Psychology students wearing white gowns listen attentively to the patients. All the conversations take place in parallel — three students sit in the room, in front of them three patients, and behind them many more.

Victoria Muya is also in the room, turning around in excitement. In honor of the trip she wore a red dress and put on red lipstick. She, too, suffers from schizophrenia, which for her is characterized by chronic depression. It reached its height when her husband tired of taking care of her and left her for another woman. She has two daughters who have not visited her since she was hospitalized. Once, in another time, she worked in her aunt's grocery store. Now, she spends most of her time resting in her room and on the center's rooftop balcony on the third floor, giving herself up to the caresses of the sun.

Section Heading: The World Can Change in a Moment

Roman Bernas’s illness first appeared fifteen years ago, during the third year of his studies in the university’s faculty of engineering. He has two brothers and two sisters — Priscilla and Florence — both of whom are diagnosed with the same disease. In their youth, they were raped by one of their neighbors. The youngest sister, Florence, remains with Roman at the center. Priscilla was released. Roman came to the center almost ten years ago, not knowing that his sister lived at the other end of the hall. He also does not remember that in the past they used to have sexual relations, even when their mother was at home.

Milagros-Seyan, Dr. Dela Llana’s daughter, who has run the day-to-day operations at the center since 2005, told me that Roman is the most difficult patient. “Roman is very unpredictable,” she said. “For days on end he is content and quiet. And then, all of a sudden, his disease strikes. He lashes out and hits other patients.” Seyan explained that his violent outbursts are the reason why he spends most of his time in solitary confinement.

The local residents know of the center's activities; it has become famous in the surrounding region. In the beginning, the center only accepted people suffering from mental illness. But over the years, Dr. Dela Llana decided also to rehabilitate those addicted to drugs. “The mentally ill generally arrive at their families’ initiative,” the doctor said. “However, the local police in Iloilo bring the patients suffering from addiction to drugs or alcohol, and they are the ones who recommend needy patients to me. Rarely, when there is no space left in the center and a new patient comes who requires urgent help, I'm forced to release a different patient who has improved. These are the most disappointing situations, because it is so important to me to lighten the load on the families as much as possible; if only I could satisfy everyone.”

One of the new addicts in the center is Rotehel Barrera. Barrera is addicted to shabu, a type of narcotic that is widely used in the Philippines and throughout Southeast Asia. He has been addicted for five years. In order to buy drugs, Barrera would often steal electronics from his parents’ home and even sell his blood to a blood bank. Last year his father suffered a stroke, and the family believes that there is connection between Barrera's decline over the past year and his father’s health.

His behavior is characterized by extreme emotional states. One minute he is able to focus on a complicated move in chess, and the next he is violent and dangerous to those around him. He will attack and provoke anyone nearby. In such situations, workers are forced to call for his mother and sister to remind him why he is hospitalized.

Nevertheless, Barrera does not understand why he is kept at the center. He announces again and again that “even the bird in the cage wants to go free.” Seyan insists that he is not yet ready to return to normal life. “The moment that he decides to take matters into his own hands and to stop the pain he is causing himself and his family, then he will succeed in being rehabilitated,” she explained. “For now, whenever he had an opportunity to take drugs, he did not hesitate.”

Section Heading: Missing Mother

A new morning at the center. Julio, Roman, and other patients go up to the attic. There, they will receive private therapy from the psychology students who provide them with the attention they need and most importantly, try to help them to acquire hygienic habits. They wash them, change their dirty clothes, and trim their fingernails, all the while hoping that their situation will improve by the next visit.

Charlito Magallanes, too, has his fingernails trimmed in the attic. He has been a patient at the center for almost five years, trying to quit drugs, passing his days between serene joie de vivre and acute aggression. Magallanes’s excessive drug use caused irreversible damage and impaired the proper functioning of part of his brain. He does not recognize his mother. Basic, everyday decisions are difficult for him, especially those connected to hygiene. The medical staff are not optimistic. Most believe that Magallanes’s chances for recovery are slim and expect a long and difficult rehabilitation.

Treating patients requires medication, food, visits to the psychiatrist, and round-the-clock observation. Because of the small budget at the staff's disposal, many families of patients face a choice: whether or not to pay for their loved one's treatment themselves, thus ensuring a personalized treatment regimen that will increase the chances of recovery. When families do not have the means, or are not involved, the doctor makes up the difference from his own pocket.

The budget depends on the city and its mayor’s willingness to help. At the moment, there is a good working relationship between Dr. Dela Llana and the mayor, Jerry P. Trenas, but if another mayor is elected, the municipal funding could decrease. “I am already 81,” Dela Llana said. “What worries me more than anything else is that I could depart this world at any moment. When it happens, who will care for the center, who will invest the money?”

The Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill wants to provide running water, to install a kitchen, to enlarge the stocks of medication, to hire a staff psychiatrist, and, most of all, to build a courtyard where the patients can get fresh air.

Address: Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill, Iloilo Police Station, General Luna Street, Iloilo City

Telephone: ++63-3372381 / ++63-3374073

Mobile: ++63-9279456936

Email: siroy_gylaine@yahoo.com; mentalill_center@yahoo.com

Text Box Explaining the Condition

Schizophrenia is a widespread, chronic mental illness classified as a psychosis. The disease affects most areas of mental and social functioning: mood, sensation, perception, thought, as well as cognitive functions. Schizophrenics distance themselves from reality, think in a disorganized and illogical way, and suffer from hallucinations and delusions. The term “schizophrenia” was coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Paul Eugen Bleuler. Despite widespread misconception, schizophrenia is not “multiple personality disorder.” Schizophrenics make up 1-1.5% of the population, and are found equally among both sexes, though there are differences in the disease's appearance and characteristics. Schizophrenia strikes young people most of all: among men, the disease mostly manifests itself between the ages of fifteen to twenty-five, and in these cases there is a high likelihood of developing negative symptoms, including emotional flattening or blunting; “poverty” of speech or language, whether in content or manner; blocks (in speaking); self-neglect (poor hygiene, sloppy dressing); lack of motivation; general lack of satisfaction; and social distancing. Among women, the disease mostly manifests between the ages of 25-35, and they have a higher chance of developing positive symptoms including delusions and hallucinations. The disease is connected to a chemical imbalance in the brain, and can be aided with medication that significantly improves the condition.

All contents © copyright Amos Roger. 2024 All rights reserved

All contents © copyright Amos Roger. 2024 All rights reservedTitle: A Soulful Journey

Sub: Artist Amos Roger spent a week at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. In this unique facility, he met Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, who founded it as a refuge for those suffering from mental illness, though in fact it barely survives; Victoria, who suffers from schizophrenia and longs to see her estranged daughters; and Julio, who was stripped of all his wealth and abandoned there. Roger shares his impressions of his encounter with these admirable and sorrowful figures who spend their entire lives trapped between hallucination and reality — and it is impossible to tell which hurts more.

Text and photos: Amos Roger

Text:

Julio Belanio sits naked on an old wooden bunk bed. His back is bruised, his gaze vacant — and his thoughts in another world. He is not aware of those around him, and he does not notice the bars on the surrounding windows. The drugs he takes first thing in the morning and at night grant him a precious few moments of grace and ease the unending struggle with the disease. As usual, he refuses the nurse’s pleas to cover himself with a blanket.

Ten long years have passed since he was left by his family at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. Who knows if they would have abandoned him in this way if Julio had not been heir to what is, in local terms, a real estate fortune. Disoriented and exhausted from the schizophrenic attacks, they forced him to sign a contract dispossessing him of all his wealth, and left him on the doorstep of the facility. He has not heard a word from them since.

Section Heading: Prison of the Soul

Julio and other patients whom life has broken and bent receive aid and support from the dedicated staff of the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill, located at the southern tip of the main island in the Visayan Islands in the Philippines. It was established two decades ago by Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, and has since cared from more than 5,000 patients. Up until fourteen years ago, the center was run out of prison cells at the local police station, and patients shared cells with local criminals. Dela Llana, previously a practicing dentist, was the force behind the founding of this unique center when he served as the city's deputy mayor. Dr. Dela Llana’s interest in the mentally ill began when he treated them in his dental clinic, part of the municipal health clinic, between 1956-1980. “I learned to love ‘the people wandering in the streets,’” he said. “Those who wander among us doing nothing. I pitied them. I used to bring them food and a little money. When I was chosen as a member of the city council in the eighties, I decided to start a project for those people: a mental health center.” When he failed to find funding for the project, he related, he made up the difference from his own salary.

Economic problems and the difficulty of finding a home for the patients led to prison cells in the local police headquarters serving as a makeshift facility. In order to have time with the patients, Dr. Dela Llana’s workers would bribe the prisoners with cigarettes and sweets — so that, if only for a few moments, they would be occupied with something else. During this time, the staff washed the inmates, and thanks to the medication they gave them, allowed the patients to have “a normal life.” The first signs of change appeared when they began receiving government support: a grant of 237,000 pesos, thanks to which they succeeded in building a six-room structure. At the same time, the city of Iloilo paid for the salaries of fourteen therapists. Only years later did Dr. Dela Llana succeed in building two more floors, the last paid for from his own pocket.

Section Heading: Forecast: No Change

Patients meet with a licensed psychiatrist once a month at the Done-Benito government hospital. The hospital is a short distance away, and during the journey Julio and his friends receive a small, fleeting taste of the world outside. During the ride, absolute silence reigns in the car, and frozen glances stare at the sights through the windows. But on the inside — spiritual turmoil and a powerful longing to become once again a part of those scenes.

When they arrive at the hospital, an interminable line stretches down the hallway, and even the room itself is too small. Privacy is nonexistent. Psychology students wearing white gowns listen attentively to the patients. All the conversations take place in parallel — three students sit in the room, in front of them three patients, and behind them many more.

Victoria Muya is also in the room, turning around in excitement. In honor of the trip she wore a red dress and put on red lipstick. She, too, suffers from schizophrenia, which for her is characterized by chronic depression. It reached its height when her husband tired of taking care of her and left her for another woman. She has two daughters who have not visited her since she was hospitalized. Once, in another time, she worked in her aunt's grocery store. Now, she spends most of her time resting in her room and on the center's rooftop balcony on the third floor, giving herself up to the caresses of the sun.

Section Heading: The World Can Change in a Moment

Roman Bernas’s illness first appeared fifteen years ago, during the third year of his studies in the university’s faculty of engineering. He has two brothers and two sisters — Priscilla and Florence — both of whom are diagnosed with the same disease. In their youth, they were raped by one of their neighbors. The youngest sister, Florence, remains with Roman at the center. Priscilla was released. Roman came to the center almost ten years ago, not knowing that his sister lived at the other end of the hall. He also does not remember that in the past they used to have sexual relations, even when their mother was at home.

Milagros-Seyan, Dr. Dela Llana’s daughter, who has run the day-to-day operations at the center since 2005, told me that Roman is the most difficult patient. “Roman is very unpredictable,” she said. “For days on end he is content and quiet. And then, all of a sudden, his disease strikes. He lashes out and hits other patients.” Seyan explained that his violent outbursts are the reason why he spends most of his time in solitary confinement.

The local residents know of the center's activities; it has become famous in the surrounding region. In the beginning, the center only accepted people suffering from mental illness. But over the years, Dr. Dela Llana decided also to rehabilitate those addicted to drugs. “The mentally ill generally arrive at their families’ initiative,” the doctor said. “However, the local police in Iloilo bring the patients suffering from addiction to drugs or alcohol, and they are the ones who recommend needy patients to me. Rarely, when there is no space left in the center and a new patient comes who requires urgent help, I'm forced to release a different patient who has improved. These are the most disappointing situations, because it is so important to me to lighten the load on the families as much as possible; if only I could satisfy everyone.”

One of the new addicts in the center is Rotehel Barrera. Barrera is addicted to shabu, a type of narcotic that is widely used in the Philippines and throughout Southeast Asia. He has been addicted for five years. In order to buy drugs, Barrera would often steal electronics from his parents’ home and even sell his blood to a blood bank. Last year his father suffered a stroke, and the family believes that there is connection between Barrera's decline over the past year and his father’s health.

His behavior is characterized by extreme emotional states. One minute he is able to focus on a complicated move in chess, and the next he is violent and dangerous to those around him. He will attack and provoke anyone nearby. In such situations, workers are forced to call for his mother and sister to remind him why he is hospitalized.

Nevertheless, Barrera does not understand why he is kept at the center. He announces again and again that “even the bird in the cage wants to go free.” Seyan insists that he is not yet ready to return to normal life. “The moment that he decides to take matters into his own hands and to stop the pain he is causing himself and his family, then he will succeed in being rehabilitated,” she explained. “For now, whenever he had an opportunity to take drugs, he did not hesitate.”

Section Heading: Missing Mother

A new morning at the center. Julio, Roman, and other patients go up to the attic. There, they will receive private therapy from the psychology students who provide them with the attention they need and most importantly, try to help them to acquire hygienic habits. They wash them, change their dirty clothes, and trim their fingernails, all the while hoping that their situation will improve by the next visit.

Charlito Magallanes, too, has his fingernails trimmed in the attic. He has been a patient at the center for almost five years, trying to quit drugs, passing his days between serene joie de vivre and acute aggression. Magallanes’s excessive drug use caused irreversible damage and impaired the proper functioning of part of his brain. He does not recognize his mother. Basic, everyday decisions are difficult for him, especially those connected to hygiene. The medical staff are not optimistic. Most believe that Magallanes’s chances for recovery are slim and expect a long and difficult rehabilitation.

Treating patients requires medication, food, visits to the psychiatrist, and round-the-clock observation. Because of the small budget at the staff's disposal, many families of patients face a choice: whether or not to pay for their loved one's treatment themselves, thus ensuring a personalized treatment regimen that will increase the chances of recovery. When families do not have the means, or are not involved, the doctor makes up the difference from his own pocket.

The budget depends on the city and its mayor’s willingness to help. At the moment, there is a good working relationship between Dr. Dela Llana and the mayor, Jerry P. Trenas, but if another mayor is elected, the municipal funding could decrease. “I am already 81,” Dela Llana said. “What worries me more than anything else is that I could depart this world at any moment. When it happens, who will care for the center, who will invest the money?”

The Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill wants to provide running water, to install a kitchen, to enlarge the stocks of medication, to hire a staff psychiatrist, and, most of all, to build a courtyard where the patients can get fresh air.

Address: Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill, Iloilo Police Station, General Luna Street, Iloilo City

Telephone: ++63-3372381 / ++63-3374073

Mobile: ++63-9279456936

Email: siroy_gylaine@yahoo.com; mentalill_center@yahoo.com

Text Box Explaining the Condition

Schizophrenia is a widespread, chronic mental illness classified as a psychosis. The disease affects most areas of mental and social functioning: mood, sensation, perception, thought, as well as cognitive functions. Schizophrenics distance themselves from reality, think in a disorganized and illogical way, and suffer from hallucinations and delusions. The term “schizophrenia” was coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Paul Eugen Bleuler. Despite widespread misconception, schizophrenia is not “multiple personality disorder.” Schizophrenics make up 1-1.5% of the population, and are found equally among both sexes, though there are differences in the disease's appearance and characteristics. Schizophrenia strikes young people most of all: among men, the disease mostly manifests itself between the ages of fifteen to twenty-five, and in these cases there is a high likelihood of developing negative symptoms, including emotional flattening or blunting; “poverty” of speech or language, whether in content or manner; blocks (in speaking); self-neglect (poor hygiene, sloppy dressing); lack of motivation; general lack of satisfaction; and social distancing. Among women, the disease mostly manifests between the ages of 25-35, and they have a higher chance of developing positive symptoms including delusions and hallucinations. The disease is connected to a chemical imbalance in the brain, and can be aided with medication that significantly improves the condition.

All contents © copyright Amos Roger. 2024 All rights reserved

All contents © copyright Amos Roger. 2024 All rights reservedTitle: A Soulful Journey

Sub: Artist Amos Roger spent a week at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. In this unique facility, he met Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, who founded it as a refuge for those suffering from mental illness, though in fact it barely survives; Victoria, who suffers from schizophrenia and longs to see her estranged daughters; and Julio, who was stripped of all his wealth and abandoned there. Roger shares his impressions of his encounter with these admirable and sorrowful figures who spend their entire lives trapped between hallucination and reality — and it is impossible to tell which hurts more.

Text and photos: Amos Roger

Text:

Julio Belanio sits naked on an old wooden bunk bed. His back is bruised, his gaze vacant — and his thoughts in another world. He is not aware of those around him, and he does not notice the bars on the surrounding windows. The drugs he takes first thing in the morning and at night grant him a precious few moments of grace and ease the unending struggle with the disease. As usual, he refuses the nurse’s pleas to cover himself with a blanket.

Ten long years have passed since he was left by his family at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. Who knows if they would have abandoned him in this way if Julio had not been heir to what is, in local terms, a real estate fortune. Disoriented and exhausted from the schizophrenic attacks, they forced him to sign a contract dispossessing him of all his wealth, and left him on the doorstep of the facility. He has not heard a word from them since.

Section Heading: Prison of the Soul

Julio and other patients whom life has broken and bent receive aid and support from the dedicated staff of the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill, located at the southern tip of the main island in the Visayan Islands in the Philippines. It was established two decades ago by Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, and has since cared from more than 5,000 patients. Up until fourteen years ago, the center was run out of prison cells at the local police station, and patients shared cells with local criminals. Dela Llana, previously a practicing dentist, was the force behind the founding of this unique center when he served as the city's deputy mayor. Dr. Dela Llana’s interest in the mentally ill began when he treated them in his dental clinic, part of the municipal health clinic, between 1956-1980. “I learned to love ‘the people wandering in the streets,’” he said. “Those who wander among us doing nothing. I pitied them. I used to bring them food and a little money. When I was chosen as a member of the city council in the eighties, I decided to start a project for those people: a mental health center.” When he failed to find funding for the project, he related, he made up the difference from his own salary.

Economic problems and the difficulty of finding a home for the patients led to prison cells in the local police headquarters serving as a makeshift facility. In order to have time with the patients, Dr. Dela Llana’s workers would bribe the prisoners with cigarettes and sweets — so that, if only for a few moments, they would be occupied with something else. During this time, the staff washed the inmates, and thanks to the medication they gave them, allowed the patients to have “a normal life.” The first signs of change appeared when they began receiving government support: a grant of 237,000 pesos, thanks to which they succeeded in building a six-room structure. At the same time, the city of Iloilo paid for the salaries of fourteen therapists. Only years later did Dr. Dela Llana succeed in building two more floors, the last paid for from his own pocket.

Section Heading: Forecast: No Change

Patients meet with a licensed psychiatrist once a month at the Done-Benito government hospital. The hospital is a short distance away, and during the journey Julio and his friends receive a small, fleeting taste of the world outside. During the ride, absolute silence reigns in the car, and frozen glances stare at the sights through the windows. But on the inside — spiritual turmoil and a powerful longing to become once again a part of those scenes.

When they arrive at the hospital, an interminable line stretches down the hallway, and even the room itself is too small. Privacy is nonexistent. Psychology students wearing white gowns listen attentively to the patients. All the conversations take place in parallel — three students sit in the room, in front of them three patients, and behind them many more.

Victoria Muya is also in the room, turning around in excitement. In honor of the trip she wore a red dress and put on red lipstick. She, too, suffers from schizophrenia, which for her is characterized by chronic depression. It reached its height when her husband tired of taking care of her and left her for another woman. She has two daughters who have not visited her since she was hospitalized. Once, in another time, she worked in her aunt's grocery store. Now, she spends most of her time resting in her room and on the center's rooftop balcony on the third floor, giving herself up to the caresses of the sun.

Section Heading: The World Can Change in a Moment

Roman Bernas’s illness first appeared fifteen years ago, during the third year of his studies in the university’s faculty of engineering. He has two brothers and two sisters — Priscilla and Florence — both of whom are diagnosed with the same disease. In their youth, they were raped by one of their neighbors. The youngest sister, Florence, remains with Roman at the center. Priscilla was released. Roman came to the center almost ten years ago, not knowing that his sister lived at the other end of the hall. He also does not remember that in the past they used to have sexual relations, even when their mother was at home.

Milagros-Seyan, Dr. Dela Llana’s daughter, who has run the day-to-day operations at the center since 2005, told me that Roman is the most difficult patient. “Roman is very unpredictable,” she said. “For days on end he is content and quiet. And then, all of a sudden, his disease strikes. He lashes out and hits other patients.” Seyan explained that his violent outbursts are the reason why he spends most of his time in solitary confinement.

The local residents know of the center's activities; it has become famous in the surrounding region. In the beginning, the center only accepted people suffering from mental illness. But over the years, Dr. Dela Llana decided also to rehabilitate those addicted to drugs. “The mentally ill generally arrive at their families’ initiative,” the doctor said. “However, the local police in Iloilo bring the patients suffering from addiction to drugs or alcohol, and they are the ones who recommend needy patients to me. Rarely, when there is no space left in the center and a new patient comes who requires urgent help, I'm forced to release a different patient who has improved. These are the most disappointing situations, because it is so important to me to lighten the load on the families as much as possible; if only I could satisfy everyone.”

One of the new addicts in the center is Rotehel Barrera. Barrera is addicted to shabu, a type of narcotic that is widely used in the Philippines and throughout Southeast Asia. He has been addicted for five years. In order to buy drugs, Barrera would often steal electronics from his parents’ home and even sell his blood to a blood bank. Last year his father suffered a stroke, and the family believes that there is connection between Barrera's decline over the past year and his father’s health.

His behavior is characterized by extreme emotional states. One minute he is able to focus on a complicated move in chess, and the next he is violent and dangerous to those around him. He will attack and provoke anyone nearby. In such situations, workers are forced to call for his mother and sister to remind him why he is hospitalized.

Nevertheless, Barrera does not understand why he is kept at the center. He announces again and again that “even the bird in the cage wants to go free.” Seyan insists that he is not yet ready to return to normal life. “The moment that he decides to take matters into his own hands and to stop the pain he is causing himself and his family, then he will succeed in being rehabilitated,” she explained. “For now, whenever he had an opportunity to take drugs, he did not hesitate.”

Section Heading: Missing Mother

A new morning at the center. Julio, Roman, and other patients go up to the attic. There, they will receive private therapy from the psychology students who provide them with the attention they need and most importantly, try to help them to acquire hygienic habits. They wash them, change their dirty clothes, and trim their fingernails, all the while hoping that their situation will improve by the next visit.

Charlito Magallanes, too, has his fingernails trimmed in the attic. He has been a patient at the center for almost five years, trying to quit drugs, passing his days between serene joie de vivre and acute aggression. Magallanes’s excessive drug use caused irreversible damage and impaired the proper functioning of part of his brain. He does not recognize his mother. Basic, everyday decisions are difficult for him, especially those connected to hygiene. The medical staff are not optimistic. Most believe that Magallanes’s chances for recovery are slim and expect a long and difficult rehabilitation.

Treating patients requires medication, food, visits to the psychiatrist, and round-the-clock observation. Because of the small budget at the staff's disposal, many families of patients face a choice: whether or not to pay for their loved one's treatment themselves, thus ensuring a personalized treatment regimen that will increase the chances of recovery. When families do not have the means, or are not involved, the doctor makes up the difference from his own pocket.

The budget depends on the city and its mayor’s willingness to help. At the moment, there is a good working relationship between Dr. Dela Llana and the mayor, Jerry P. Trenas, but if another mayor is elected, the municipal funding could decrease. “I am already 81,” Dela Llana said. “What worries me more than anything else is that I could depart this world at any moment. When it happens, who will care for the center, who will invest the money?”

The Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill wants to provide running water, to install a kitchen, to enlarge the stocks of medication, to hire a staff psychiatrist, and, most of all, to build a courtyard where the patients can get fresh air.

Address: Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill, Iloilo Police Station, General Luna Street, Iloilo City

Telephone: ++63-3372381 / ++63-3374073

Mobile: ++63-9279456936

Email: siroy_gylaine@yahoo.com; mentalill_center@yahoo.com

Text Box Explaining the Condition

Schizophrenia is a widespread, chronic mental illness classified as a psychosis. The disease affects most areas of mental and social functioning: mood, sensation, perception, thought, as well as cognitive functions. Schizophrenics distance themselves from reality, think in a disorganized and illogical way, and suffer from hallucinations and delusions. The term “schizophrenia” was coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Paul Eugen Bleuler. Despite widespread misconception, schizophrenia is not “multiple personality disorder.” Schizophrenics make up 1-1.5% of the population, and are found equally among both sexes, though there are differences in the disease's appearance and characteristics. Schizophrenia strikes young people most of all: among men, the disease mostly manifests itself between the ages of fifteen to twenty-five, and in these cases there is a high likelihood of developing negative symptoms, including emotional flattening or blunting; “poverty” of speech or language, whether in content or manner; blocks (in speaking); self-neglect (poor hygiene, sloppy dressing); lack of motivation; general lack of satisfaction; and social distancing. Among women, the disease mostly manifests between the ages of 25-35, and they have a higher chance of developing positive symptoms including delusions and hallucinations. The disease is connected to a chemical imbalance in the brain, and can be aided with medication that significantly improves the condition.

All contents © copyright Amos Roger. 2024 All rights reserved

All contents © copyright Amos Roger. 2024 All rights reservedTitle: A Soulful Journey

Sub: Artist Amos Roger spent a week at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. In this unique facility, he met Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, who founded it as a refuge for those suffering from mental illness, though in fact it barely survives; Victoria, who suffers from schizophrenia and longs to see her estranged daughters; and Julio, who was stripped of all his wealth and abandoned there. Roger shares his impressions of his encounter with these admirable and sorrowful figures who spend their entire lives trapped between hallucination and reality — and it is impossible to tell which hurts more.

Text and photos: Amos Roger

Text:

Julio Belanio sits naked on an old wooden bunk bed. His back is bruised, his gaze vacant — and his thoughts in another world. He is not aware of those around him, and he does not notice the bars on the surrounding windows. The drugs he takes first thing in the morning and at night grant him a precious few moments of grace and ease the unending struggle with the disease. As usual, he refuses the nurse’s pleas to cover himself with a blanket.

Ten long years have passed since he was left by his family at the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill in the Philippine city of Iloilo. Who knows if they would have abandoned him in this way if Julio had not been heir to what is, in local terms, a real estate fortune. Disoriented and exhausted from the schizophrenic attacks, they forced him to sign a contract dispossessing him of all his wealth, and left him on the doorstep of the facility. He has not heard a word from them since.

Section Heading: Prison of the Soul

Julio and other patients whom life has broken and bent receive aid and support from the dedicated staff of the Center for the Care of the Mentally-Ill, located at the southern tip of the main island in the Visayan Islands in the Philippines. It was established two decades ago by Dr. Guillermo Dela Llana, and has since cared from more than 5,000 patients. Up until fourteen years ago, the center was run out of prison cells at the local police station, and patients shared cells with local criminals. Dela Llana, previously a practicing dentist, was the force behind the founding of this unique center when he served as the city's deputy mayor. Dr. Dela Llana’s interest in the mentally ill began when he treated them in his dental clinic, part of the municipal health clinic, between 1956-1980. “I learned to love ‘the people wandering in the streets,’” he said. “Those who wander among us doing nothing. I pitied them. I used to bring them food and a little money. When I was chosen as a member of the city council in the eighties, I decided to start a project for those people: a mental health center.” When he failed to find funding for the project, he related, he made up the difference from his own salary.